AirDrop became very popular in China recently, for the simple reason that the function completely disguises the sender’s contact details. As AirDrop transmission does not take place via the internet or cellular phone network, but from iPhone to iPhone via Bluetooth identification and a local Wi-Fi network, it’s extremely difficult, if not impossible, for authorities to identify senders. This allowed protesters to exchange important messages, memes, and photos with each other without the police being able to crack the networks.

With the launch of iOS 16.1.1 around a year ago, however, Apple put in place a time limit of 10 minutes when sharing connections with Everyone, rather than the default Contacts Only setting. The official line was that this move was intended to combat AirDrop spam and abuse, but the suspicion was that Apple was acceding to the wishes of the Chinese government–particularly as the change applied first in China.

Now a Chinese state-licensed security company from Beijing claims (via Bloomberg) it has successfully cracked the system and obtained the contact details of an AirDrop sender. The firm says its experts have found log data for the AirDrop process on a recipient’s iPhone; the device name of the sender’s iPhone, along with their email and telephone number, is saved on the target iPhone during data transfer. Although the latter two details are converted into hash values, the security company has found a method to convert these hash values into readable text.

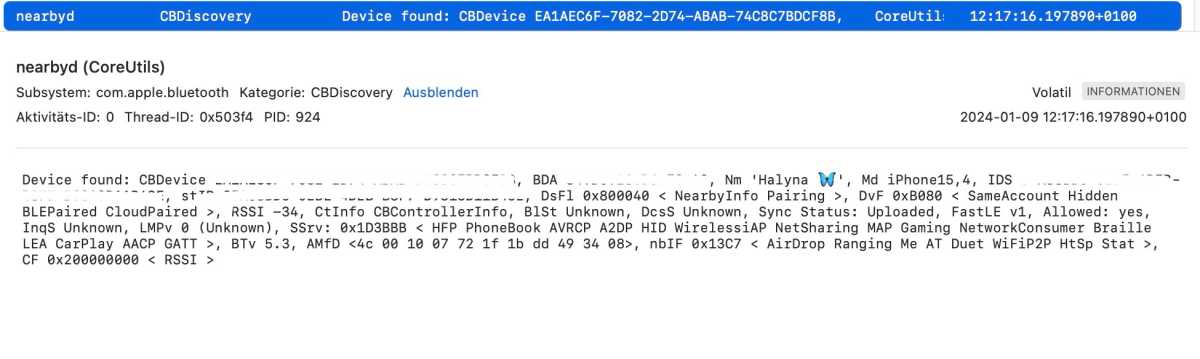

We can confirm parts of this claim. We launched the console on our Mac and AirDropped a file to it from an iPhone, discovering from the console log data that the “sharingd” process is responsible for AirDrop. This contains a dedicated sub-process called “AirDrop,” but several other sub-processes were also active during the file transfer. We found the name of our iPhone in one of the sub-processes, along with the strength of the Bluetooth signal.

Device details in the console logs.

Halyna Kubiv

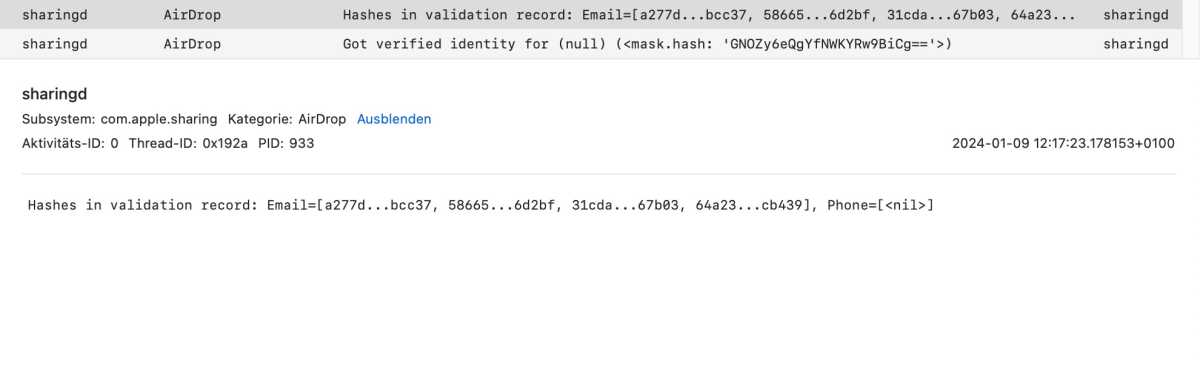

The “AirDrop” sub-process actually stores the hash values for the email and phone number belonging to the contacted iPhone (see screenshot), but we were unable to access the plain text.

Console logs during the AirDrop transfer

.Halyna Kubiv

Last but not least, it should be noted that our Mac and our iPhone are trusted devices, otherwise the AirDrop transfer would not work at all. Even with unknown contacts, the recipient must first authorize the data transfer; no foreign files are transferred without their knowledge. If the reports are true, AirDrop is a threat to dissidents in authoritarian states, as they believe they can remain anonymous when exchanging files.

Why didn’t Apple fix the flaw?

Security researchers have been warning Apple since at least 2019 that the AirDrop protocol is flawed and can be cracked. In August 2021, the group led by Alexander Heinrich at TU Darmstadt presented a much more secure alternative called Private Drop.

The problem with AirDrop is that the protocol requests the address and phone number verified via the Apple ID from the sender’s device and the recipient’s device when establishing a connection if these are not in the address book of both parties. Although they are stored as hash values, they are fairly easy to decipher: the phone number consists only of digits and is easy to decode using a brute-force attack. For emails, attackers guess the usual alias structures, then search for possible matches in dictionaries and databases of leaked emails.

According to Heinrich, it was only a matter of time before the security gaps in AirDrop were abused. However, the researchers have so far only intercepted the data during transmission attempts. The fact that the personal data of AirDrop contacts is stored locally on the iPhone was previously unknown.

Heinrich says Apple reportedly contacted the researchers from Darmstadt about the loophole way back when iOS 16 was still in development. However, Heinrich was unable to find any significant changes to the transfer protocol security. Apple’s difficulty would be that the newer and more secure version of the AirDrop protocol would not be backward compatible with older iOS versions, he added.

This article originally appeared on Macwelt and was translated and edited by David Price.